- Introducing the Theorem

- Prerequisite Knowledge

- How to Teach Students

- Application Problems

Introducing the Pythagorean Theorem

The Pythagorean Theorem stands as a cornerstone of middle school mathematics, offering a gateway to understanding the relationships between the sides of right triangles. And yet, I have found that students can frequently do quite well and yet not truly understand it. Most all can plug and chug into the algorithm for very typical solve for a missing side type question, but then, when asked anything that requires more understanding, they can be tripped up pretty easily.

I try to start with an activity that allows them to puzzle various sized squares together to see if they can figure out the theorem on their own before I tell it to them. And some actually can. When I ask why some of the pieces with various side lengths were able to fit together, I hear comments like, “3 + 4 does not equal 5 but I noticed that the squares of 3 and 4 added together do equal the square of 5.”

The one thing I really want them to truly understand is that a side length squared is really an area. Seems so simple and yet when a students sees the Pythagorean Theorem I want them to not just see it as a2+b2=c2 but rather to think “leg area plus leg area equals the hypotenuse area.” One of the best ways I have found to show this visually is by letting them experiment with a proof without words like this from Geogebra.

Prerequisite Knowledge

Oddly enough, when I know I am about to teach Pythagorean Theorem, I actually warm up with a mini lesson on squares. I give students various squares and have them practice working backwards from their areas to their side length. So many students want to divide by four and getting them to understand that that is only appropriate when given the perimeter of a square and getting them to find the square root instead is a bit of a struggle every year. It’s worth the time though because I know that Pythagorean Theorem is really all about area.

Of course, I do remind students about all those various types of triangles they were previously taught about and we finally settle into the one that is our focus: the right triangle. We discuss the vocabulary of the triangle’s legs noticing that where they join forms the right angle and outward from that right angle is the longest side, the hypotenuse. We practice labelling some triangles so that everyone is clear on where “c” needs to be. And then we are ready to dive into using the theorem to solve.

How to Teach Students

I taught using the algorithm to solve for years. Step by step, solving algebraically, and finally finding the square root at the end. It worked great…or so I thought. Truthfully, to no surprise to any teacher reading this, a large number of students were not super fans of step by step algebraic solving. Now, looking back, I don’t think I really did even the ones that did successfully use the algorithm a great service in their conceptual understanding. Sure, they could solve straight forward problems, but, when they encountered something less formulaic, they were often stumped.

I’m not sure when exactly I abandoned teaching algebraically, but one year I just stopped cold turkey. Now I exclusively teach by drawing the model of the Pythagorean Theorem and it has seriously worked so much better! Eventually, many tend to drop it on their own and just start writing the squared numbers and not actually drawing the squares, but a significant number never do and I don’t encourage them to. I think the conceptual knowledge is more deeply ingrained every single time a student draws an attached square onto a triangle’s side and writes in its area. Then, when I ask the area of one of the squares and not its side length, they are so much less likely to give me a side length or fall for a distractor answer.

Application Problems

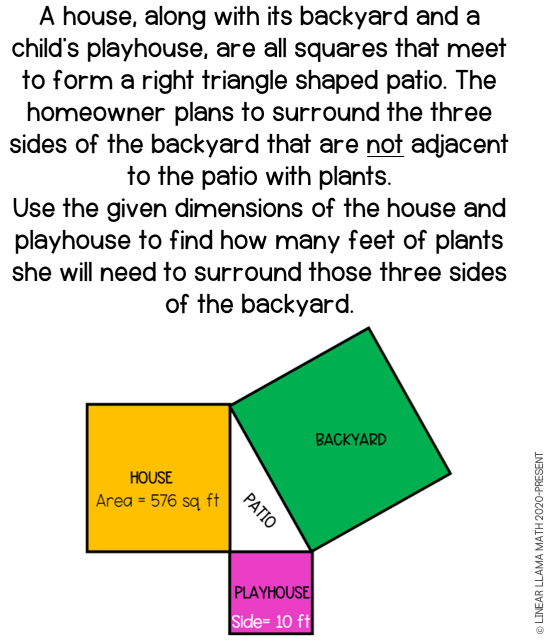

As soon as we get past the basics of solving, I like to have a day focused on application problems. I think it is a right of passage in Pythagorean Theorem to find the length of the ladder leaning against a building or the length of the leaning over part of a broken tree or pole. So of course, I show problems like that and we solve them. I like to push them a bit further though so I created a series of questions that have an extra layer of thinking in them and that don’t simply solve for a missing side. Below is an example of one from my resource.

If you are also looking for more problems to make students not just solve a a missing leg or the hypotenuse, I think you’ll enjoy using my Pythagorean Theorem Task Cards with your classes. They can be used scavenger hunt style also if you post them around on the walls. Every full size, full color card has the answer to another question on it so it is self-checking. I like to make about 6 sets and put them in plastic page sleeves and let table or station groups use dry erase markers on them to solve. If I want students to work individually, I can post the post the pdf to Google ClassroomTM.

This topic continues to be one of my favorites to teach and I really enjoy using these questions. If you try them, I hope you do too.

You must be logged in to post a comment.